Credit union lending was in the spotlight as TruStage director and chief economist Steven Rick presented an Economic and Credit Union Update sponsored by Origence. Coming less than 24 hours after President Trump announced sweeping economic tariffs, Rick helped make sense of market uncertainty and outlined variables that could help credit unions understand current events and develop strategies to prepare for the future.

Auto lending is a core product for credit unions and the dynamics of that market have shifted dramatically over the past several years. Post-pandemic supply chain shortages pushed the price of new cars up and drove used car prices even higher. Year-over-year growth in used car prices peaked in 2021-2022 and has fallen sharply since then, in some cases exposing credit unions to increased collateral risk exposure. Today’s used car prices are growing at a modest 0.7%, and new car prices are shrinking slightly at -0.3%, both well below a target inflation rate of 2%. A 25% tariff on automobiles imported into the U.S., along with anticipated tariffs on car assembly components, will impact the market in several ways. In the short term, expect a spike in sales as consumers try to get ahead of price increases. In the long term, the increased complexity of supply chain logistics and the cost of shifting production to U.S. factories, even for domestically assembled vehicles, will result in higher new car prices and push demand down. Consumers who may be priced out of the new car market may then drive used car prices higher. Tariffs on auto parts mean higher repair and maintenance costs. More expensive parts will cause the cost of collision repair to jump as well, and the rising cost of car insurance won’t lag far behind.

Credit unions are currently experiencing a rare period of negative loan growth in the new car segment. New car loan growth is at a seasonally adjusted -5% year-over-year. This is the first time in this century that credit unions have seen a drop in new auto loan growth without a corresponding recession. This loan segment ordinarily grows at a long-run average of about 5%. Even more unusual is the fact that credit union used car loan balances are decreasing, landing in negative territory for all of 2024. Used car loans are arguably the cornerstone of credit union lending and negative growth in this segment is virtually unheard of in recent memory. Although improving somewhat in recent months, this category remains persistently, slightly in the red, and comes in well short of the 7% long-run growth average that credit unions have been accustomed to.

Credit union delinquency rates overall don’t seem terrible at about 1%, but that is rising and still a little bit higher than what might be considered a “natural” delinquency rate of 0.75%. This is especially notable given the very low level of unemployment that is running about half a percentage point below what is considered a full employment rate. Credit union’s net charge-offs at 0.76% are similarly about a quarter point above what would be expected. Some of this can be attributed to the denominator effect as the exuberance of record lending activity a few years ago now amortizes and pays off. That said, several current market factors are also driving these delinquency rate increases. First of all, household earnings didn’t go up as quickly as prices did, resulting in real wages falling. The other thing that went up quickly was rent, and that put additional pressure on household budgets. Additionally, student loan payment deferments are expiring, exacerbating already stretched paychecks. If that were not enough, higher interest rates on credit cards, HELOCS, and ARMs are adding to consumer woes.

Rick singled out lower-quality office property as a collateral segment particularly at risk. Even considering a return-to-office initiative, remote workers can and will negatively impact demand for office space—especially those properties perceived as lower tier and less attractive to business tenants. Vacancies are increasing, rental revenues are down, and the potential for default—strategic or otherwise—has gone up.

All these pressures are contributing to higher delinquency and charge-off numbers on credit union balance sheets, despite low unemployment. Falling used car prices could lead to an uptick in walk-away auto repos when the loan balance greatly exceeds the value of the collateral. Additionally, higher car insurance costs could trigger a secondary risk as members may be tempted to drop collision insurance.

The Federal Reserve sets interest rates to establish monetary policy focused on the dual objectives of slow growth and full employment. The policy targets a neutral interest rate of 3% – a rate that tries neither to speed up nor slow down the U.S. economy. Covid prompted the Fed to stimulate the economy with rates close to zero for a time, effectively putting the gas pedal to the floor. As the inflationary consequences of the stimulus grew, the Fed jacked rates up a few years ago to slam the brakes on rising prices. These efforts to combat inflation have been slowly and gradually reducing market pressure and dropping rates gradually to the current level of 4.3% on a trajectory towards the 3.0% target.

For the past several cycles, the Fed has been on that glide path, gradually lowering interest rates as the economy recovered from a post-pandemic, supply cycle driven high inflation period. Unemployment is below what is considered full employment, indicating some worker shortages. There are a number of economic risks that could alter that glide path, starting with the risk that the Fed is too slow in lowering interest rates. A decrease in stock and/or home prices could slow economic growth. Geopolitical turmoil, such as the war in Ukraine and other global conflicts, presents a risk to U.S. interests. The potential for a rise in energy prices could put additional pressure on the economy. Finally, the prospect of a growing trade war rounds out the list of potential pitfalls that increase the possibility of a recession and could alter the current Fed policy direction.

Looking to the future, Rick outlined a summary of policy initiatives put forward by the current administration in Washington, along with an analysis of potential consequences associated with each of the President’s proposals.

Some of the proposed changes could have entirely positive results. For example, a successful campaign to deregulate and create a more efficient federal government would likely result in lower inflation and smaller deficits while raising GDP. Conversely, Rick says that the prospect of mass deportation might do the opposite – lowering GDP while pushing inflation and deficits higher. Several of the Trump initiatives would likely lead to a mixed bag of good and bad outcomes. For example, the prospect of 10-20% universal tariffs might generate revenue that could potentially lower the federal deficit, but at the same time, those tariffs would raise prices and negatively impact domestic production. A proposal to extend the 2017 Tax Cut and Jobs Act might raise inflation and deficits but contribute to a higher GDP. The same is true for the proposal to eliminate tax on tips, overtime, and Social Security. Lastly, the downsizing of our federal workforce promises the opposite – helping with inflation and deficits but hurting GDP.

Inflation has come down, currently hovering around 2.6%. The Fed is likely to continue resisting lowering rates until inflationary pressures recede further. Until the 2% target is achieved, inflation will continue to pressure household budgets, drive up delinquency rates, labor costs, and operating expenses, and negatively impact consumer confidence.

Given the current state of uncertainty and the dynamic changes occurring in real-time, credit union strategists are urged to consider multiple possible options for the Fed to adopt in the coming months. Until recently, the most likely path forward was a continuation of the current gradual descent or glide path that would have further reduced interest rates by an additional 1.3% over the next two years. An uptick in unemployment or increasingly urgent indicators of a potential recession could accelerate that time frame and prompt the Fed to drop rates faster. Conversely, inflationary pressures brought on by persistent tariffs and the prospect of retaliatory actions by other countries could tilt the Fed towards a slower reaction, perhaps leading to a suspension of rate cuts in 2025. A bigger challenge could develop should both higher inflation and higher unemployment put competing pressure on the Fed’s key borrowing rate.

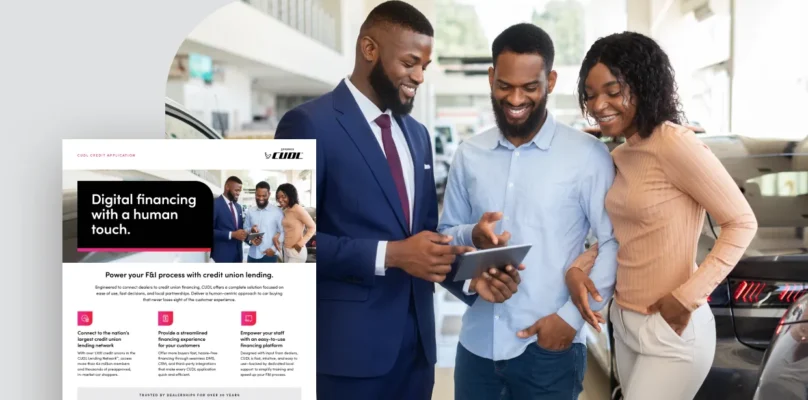

How indirect lending maximizes efficiency and member value

Why State ECU selected Origence Indirect Lending to improve efficiency, increase volumes, and grow revenue.